This post has been my debt for a long time now, primarily toward my dear colleagues at AerinX. I’ve been thinking about this topic for quite a while, collecting and organizing my thoughts, trying to create a structure and an arc that makes the story somehow digestible. My intention and goal here are to give my colleagues and everyone else a look into my way and framework of creating solutions for specific customer problems or requirements and then deciding which solution to choose of the several possible. My purpose is to make you understand the background of my everyday decisions better and ingrain this framework into our company’s culture.

The Problem

First, nail down the ultimate problem and goal of software development in general. This can be the topic of another (dozen) long article(s) or rather books, but just take this as a given for our purposes. The main goal of software development and everyone working in it is to create and build as much business value as fast and as cheap as possible. It is important to see that time and money are always limited, unlike business value. Put another way: our goal is to generate as much business value as possible within given cost and time limits. The consequence is that we’re never looking for the perfect or best solution in terms of business value only. We’re always looking for the best solution in terms of business value and cost (time and money) together!

There are an endless number of requirements, user stories, and problems to solve for every software system. For every requirement, there are several different or slightly different potential solutions that solve the problem. The two questions that I try to address in this article are the following:

- How should we think when generating different potential solutions for a requirement or problem? – This is mainly the responsibility of business analysts and software architects

- Which one to actually implement of the many potential solutions? – This is mainly the responsibility of product owners or higher-level executives

The Framework

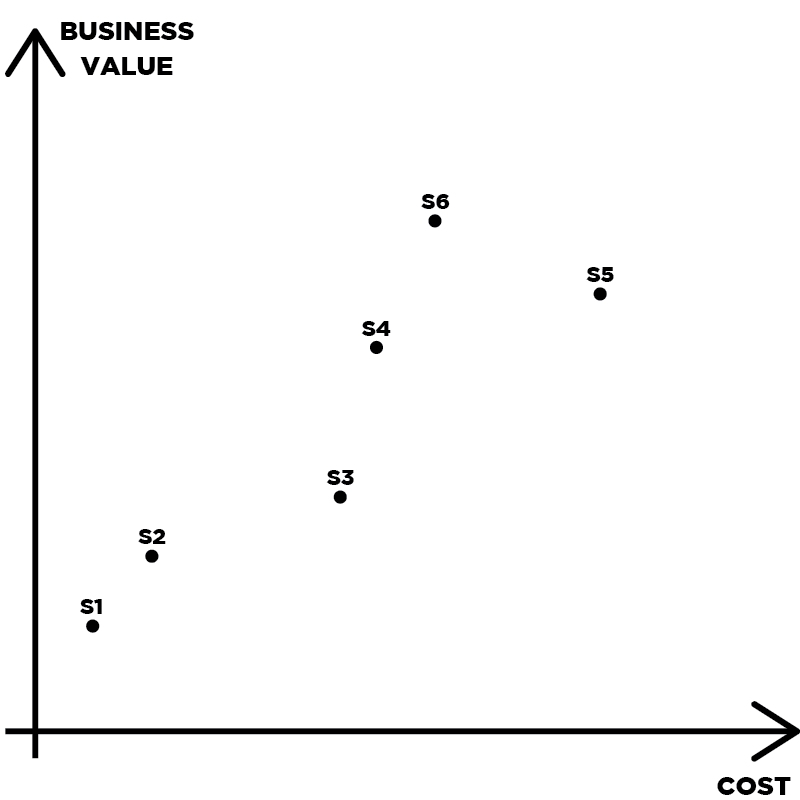

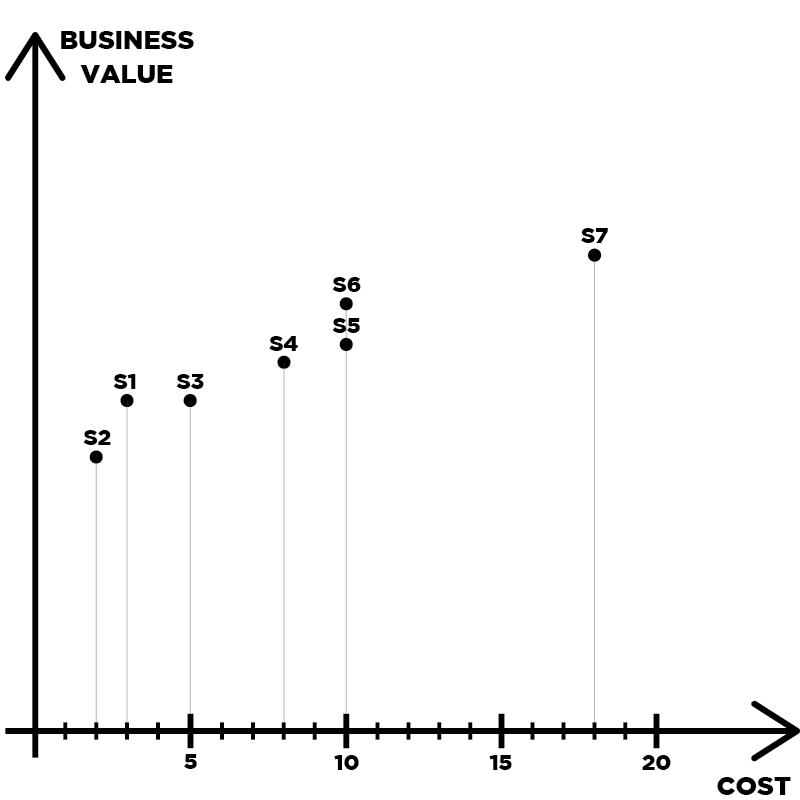

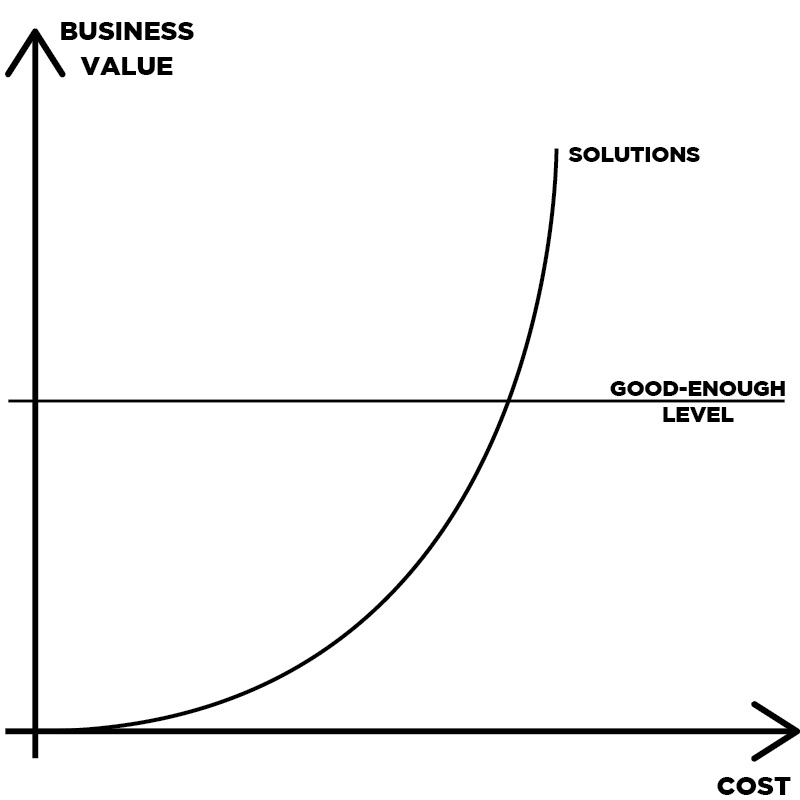

If I wanted to formulate my framework of thinking, I would say that I examine every potential solution in the cost-benefit dimensions. I very often imagine or even draw this on an actual two-dimensional coordinate-system where:

- the X-axis is the cost of building the solution

- the Y-axis is the benefit or business value of the solution for users, customers, or the company that owns the solution.

Every potential solution can and should be placed in this two-dimensional cost-benefit or cost – business value coordinate system.

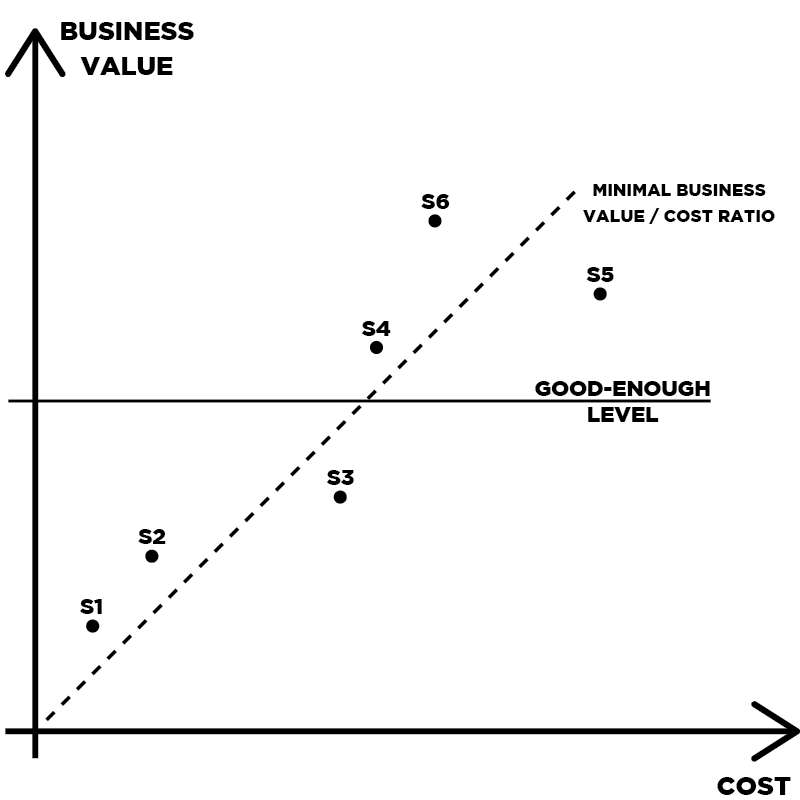

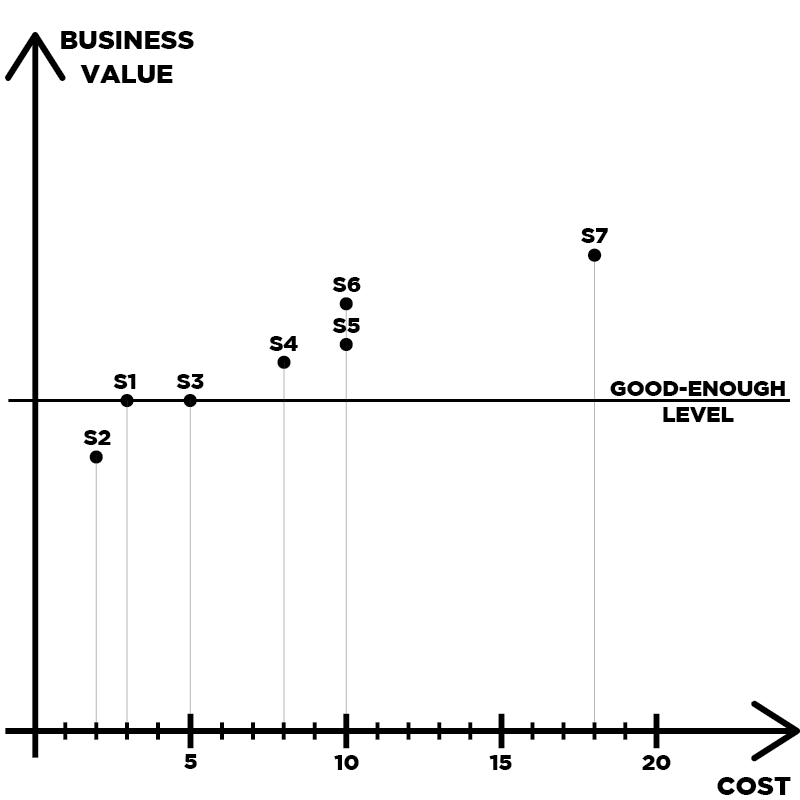

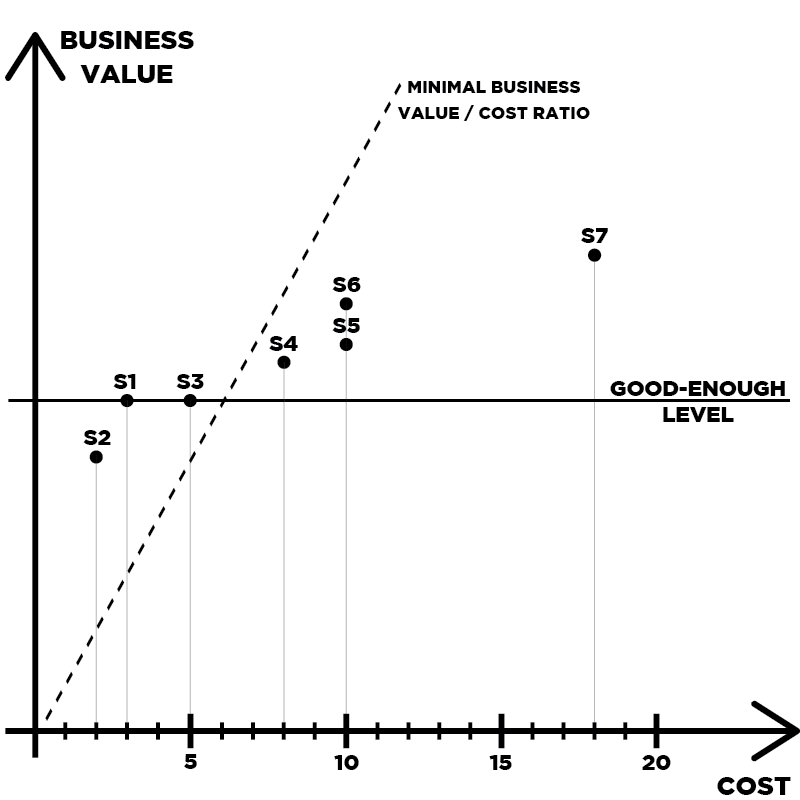

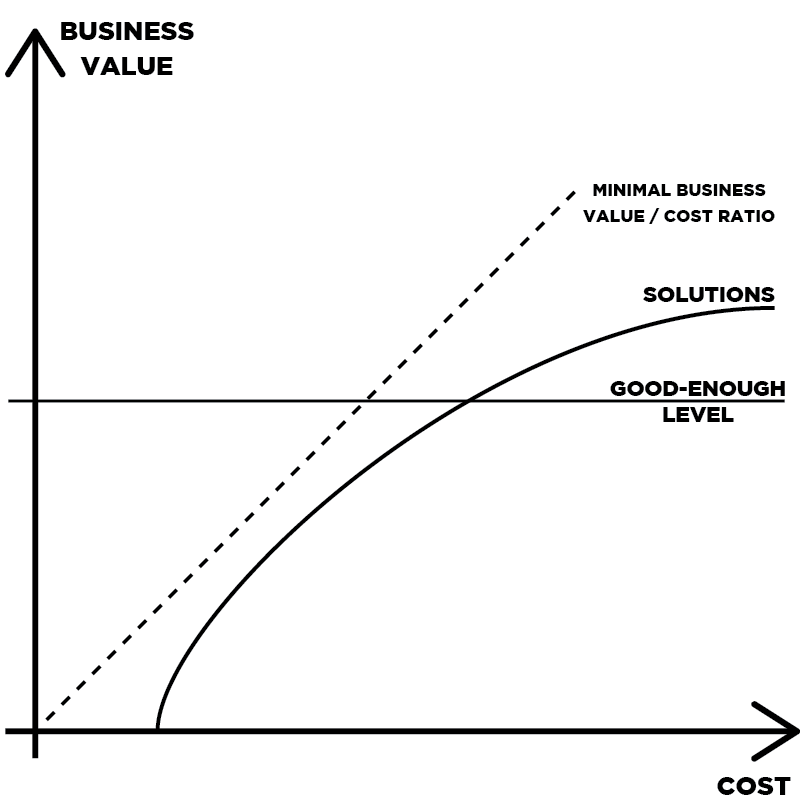

Once we have our potential solutions and we evaluated them regarding cost of development and business value, how do we pick which one to go with? To make this decision, we need two more things to determine:

- Where is the expected minimum or good-enough level of business value? To represent this on the graph, we need a horizontal line to be drawn somewhere on the business value axis.

- What minimum business value / cost ratio (or return of investment) can justify different solutions? In other words: where is the point where a solution is not worth building because of its high cost (relative to its business value)? To represent this on the graph, we draw a broken line with a certain angle from the origin.

These lines mean two things:

- Solutions not good-enough: The solutions below the good-enough line should not be built because they won’t make the user, customer, or system owner happy.

- Solutions too costly: The solutions below this line are not worth (or economic) building because they are more expensive than their business value.

So the only solutions worth considering to implement are the ones above both lines. And which should we pick from these? We can’t make a big mistake choosing the cheapest, but we can also take other considerations into account.

To summarize the steps of this process:

- Generate different solution concepts!

- Assign cost and business value to each of these! -> place them on the cost – business value coordinate system

- Determine the good-enough level of business value! -> draw a horizontal line on the business value axis

- Determine the business value / cost ratio that ensures a positive return of investment! -> draw a line from the origin with a given angle

- Exclude solutions below the good-enough business value line or the return-of-investment line!

- Pick one solution from the rest, probably the cheapest!

Theory vs Practice

This all sounds simple and straightforward, doesn’t it? Well, yes, in theory! Unfortunately, not as much in practice…

Let’s take a simple example of a requirement that we can use to illustrate the framework and the workflow. Let’s assume that we need to calculate the number of business days between two dates. This is a simple calculation in most cases, but to calculate it precisely in every case, we need to know about the so-called exception days: weekdays which are not business days (national holidays), and weekends which are business days (for instance, in Hungary there are a few Saturday workdays sometimes). The requirement is to store, access, and maintain these exception days in the system.

Now let’s try to go through the process described above!

Step #1: Generate different solution concepts

I gathered a few solutions that came to my mind the following table, describing how each solution solves the three different parts of the problem. (Please ignore the last columns for now, I’ll explain it later.)

| Solution | Storing exception days | Reading exception days for calculations | Maintaining exception days | Relative cost |

| S1 | Create a simple text file or excel file somewhere on a shared drive to store exception days in | Implement the reading of the data from the shared file when it is needed for calculations | Maintain it with simply editing the file by any user | 3 |

| S2 | Create a storage for the exception days in the backend or database | Access the data from the database, like any other data in the system | Maintain the data with the help of developers or database admins | 2 |

| S3 | Same as S2 | Same as S2 | Maintain the data with an admin maintenance feature where the user can add or delete exception days like any other simple base data | 2+3=5 |

| S4 | Same as S2 | Same as S2 | S3 with extra validations making sure there are no duplicate exception days, etc. | 5+3=8 |

| S5 | Same as S2 | Same as S2 | S3 with a fancy UI of a calendar where the user can mark the exception days by clicking on the respective days | 2+8=10 |

| S6 | Same as S2 | Same as S2 | Finding a web-site or public web-service from where we can download and store the exception days of a given year with a feature in our system | 2+8=10 |

| S7 | Same as S2 | Same as S2 | S6 (downloading data from external source) + S5 (fancy manual maintenance function) | 2+8+8=18 |

I hope this illustrates how many potential solutions can arise even for such a simple requirement. Coming up with different solutions can be extremely complex and challenging, and we can never be sure of whether there is an even better (cheaper and bigger value) solution lying out there undiscovered! But this post is long and complicated enough already, so I don’t go into further details for this step.

Step #2: Assign cost and business value to each of these

Okay, so how do I calculate the cost of building a solution? What is the unit in the cost axis in the first place? A relatively simple and suitable solution for this problem is using story points on a relative scale as they do it in Scrum Poker (see my related article about Scrum Estimations). Story points can even be translated into actual dollars if needed. To estimate the development effort or cost, you need of course to consult with technical people (software architects or developers) about the implementation.

And what about business value? What is the scale or unit of business value? And how do I determine the value of a solution on this scale? Well, the situation is even worse, actually much worse than with the cost. There is no standard or uniform way of measuring and expressing business value. Business value is something you have to determine from examining the problem or requirement and the solution from several different aspects and viewpoints. You need in-depth knowledge of the business case, the use-case, and several other factors. You need to ask the customer and the users many questions, like:

- What is the goal to reach with this requirement? Why is it important?

- How do you solve this problem now, without the feature we’re talking about?

- How many users will use this feature? How often will they use it?

- How much time and trouble would this feature save?

- What additional benefits would this feature bring to you?

- Etc.

Based on all this information, you might be able to draw a picture about the relative (or absolute) business value of the different potential solutions.

For our example of handling exception days, the answers to the questions above would look something like this:

- The goal is to calculate the number of business days accurately in different reports. Without this, certain reports would show imprecise data.

- Currently, someone has to correct the report manually in case there is an exception day in the date interval of the report.

- Lots of users generate and use such reports. Making these correct would save a lot of time currently spent fixing these manually.

- The other part of the feature, actually maintaining exception days would typically be used by only one admin user at the beginning of every year, when he administers the handful of exception days of the given year. This is a 5-10 minute task maximum, once every year.

The conclusion is that storing and using exception day data is of very high importance and business value, but this part is solved almost equally by every potential solution. On the other hand, making exception day maintenance faster, easier, and more convenient is of little value since exception day maintenance is typically only used once a year by one user for a few minutes only. Making this fully automatic would only save 5-10 mins/year for the whole company.

Now let’s try placing these solutions in our cost – business value coordinate system:

Step #3: Determine the good-enough level of business value

Based on the analysis in the previous step, we can say two things about the good-enough level of business value:

- Solving the problem of storing and using the exception day data is a must (all potential solutions solve this)

- Solving the problem of maintaining exception days is also a must, but the level and quality of the solution do not matter because it doesn’t save much time. It might be nice if exception day maintenance can be performed without the help of IT personnel (all solutions solve this, except S2)

So the line of the good-enough level could look something like this:

Step #4: Determine the business value / cost ratio that ensures a positive return of investment

To determine the business value / cost ratio, we can follow the thinking of the previous step. Putting extra effort into better, faster, and more convenient exception maintenance can hardly be justified, so the line should go like this:

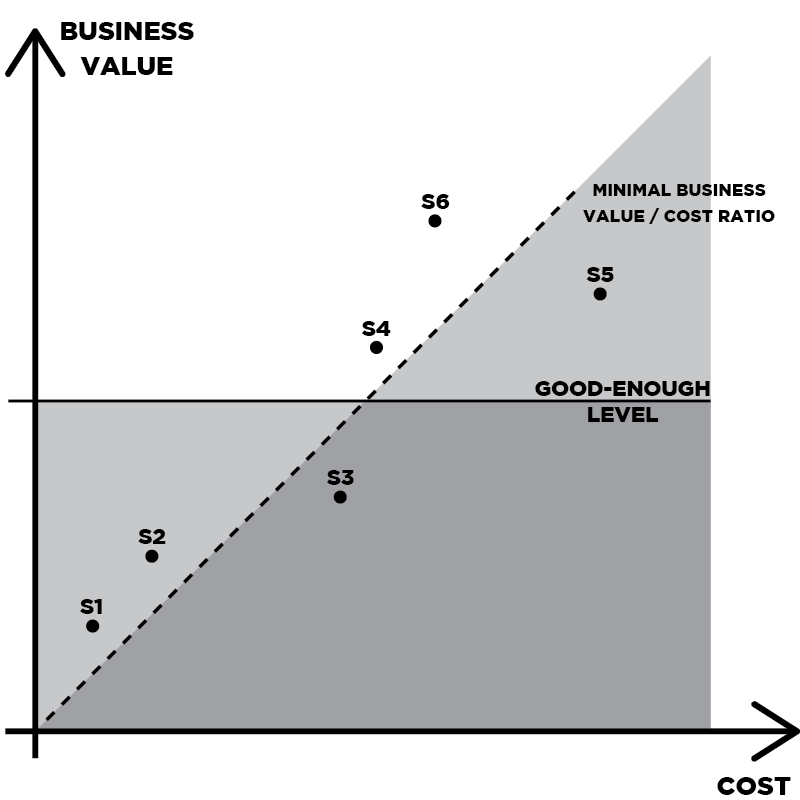

Step #5: Exclude solutions that fall below the two lines

Let’s examine which solutions should we exclude at this point:

- S2 is excluded because it doesn’t reach the good-enough business value level (because IT admins are needed for exception day maintenance)

- S4, S5, S6, and S7 are also excluded because their cost can not be justified relative to their business value. These are obviously better solutions than S1 and S3, but those additional few minutes time saving per year will most likely never return us the cost of their development.

Step #6: Pick the cheapest solution from the rest

So we are left with S1 and S3, which are similar in both business value and cost. We probably wouldn’t make a big mistake by implementing either of them. We might even consider additional, technical aspects when deciding which one to choose, for instance:

- If it is common case in our system to store certain data in external files, then S1 could be the best solution to pick.

- If this is rare and we prefer all data to be stored in the system database, then probably S3 is the best solution.

You can see that going through the steps of the workflow and organizing different solutions in this framework is not only a matter of science, exact measures, and numbers. The other significant part of it is more like experience, intuition, and a bit of art. Mainly because there are several steps where measures are difficult to set up. You can’t really get the following things exactly right:

- Business value of different solutions

- Good-enough level of business value

- Translating business value to actual dollars

- Determining the economic business value per cost ratio

Types of Curves

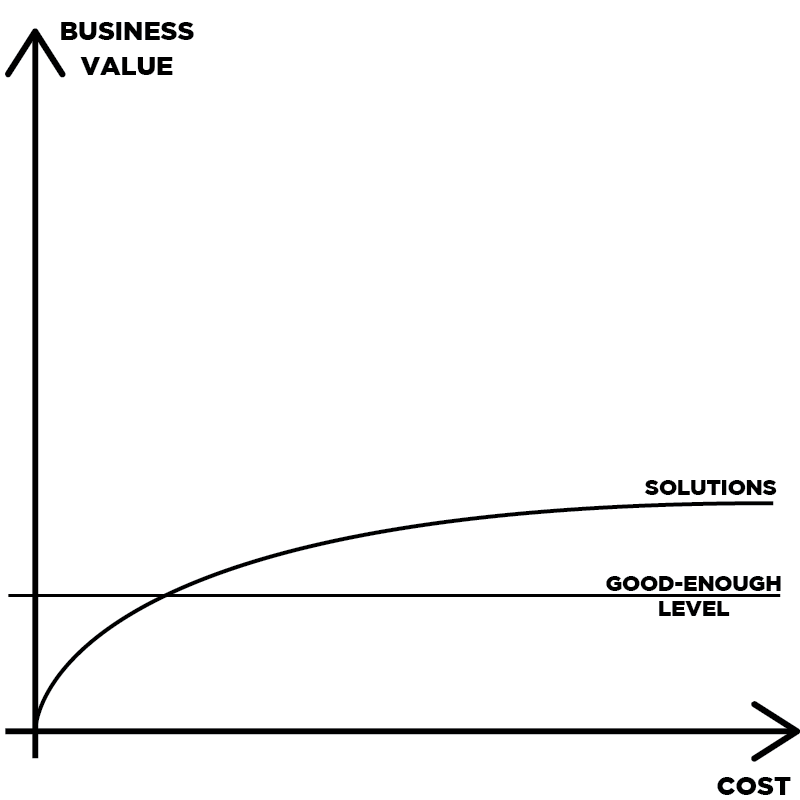

Different requirements, problems, and potential solutions can result in different curves in the cost – business value space that is worth examining.

Sometimes we can reach a good-enough solution relatively cheaply, but then it would be costly to deliver a solution of higher business value. In this case, our decision is usually easy since it is not worth going past the minimal business value solution.

Sometimes we have to invest a lot of work to reach a good-enough solution, but then we can reach higher level solutions for a little additional cost. In this case, it is worth considering investing a little more to get a solution of higher business value.

Sometimes a good-enough solution is so costly that it makes no economic sense solving the problem at all.

Additional Complexities

This process is already complex and complicated enough, but in reality, several additional aspects can make it even more difficult. Going more details into these is out of my scope now, but I collected and organized a few of these common complications.

Cost related complexities: there can be additional hidden costs above the obvious development costs that might be useful to consider when calculating cost:

- Architectural / technical debt generated: How well the solution fits into the overall architecture and technology of the system? How much refactoring effort does it cause later on?

- Support, training, and consultation efforts: How straightforward is the solution from a user experience point of view? Does it induce extra documentation (user or administrator manual), training, or support efforts?

- Troubleshooting and bug fixing efforts: How robust is the solution? How many external dependencies does it have? How likely is it that the function will break later, needing continuous efforts to fix them?

Business value related complexities:

- Business value can be a very complex phenomenon and measure itself, which combine many more aspects above the obvious (functionality): usability, availability, reliability, recoverability, performance (throughput, response time, predictability, capacity), security, etc.

- In many cases, the business value of a solution can even change in time. There might be problems where a solution is very valuable on the short term, but loses its value over the longer run (because the problem itself changes or ceases). In other cases, the problem is getting even more painful with time, increasing the business value. Sometimes a solution is good-enough now (because the system has only 30 users), but it won’t be enough two years later (for 300 users).

- The good-enough business value level is strongly context-dependent. Even if we are talking about the same requirement or function, the good-enough level can be wildly different for an iPhone OS feature used by hundreds of millions of users worldwide and for an admin feature of an in-house company software used by one or two users.

- To understand and estimate business value and its relationship with cost, it is very important for the responsible IT people (business analysts and software architects) to understand several business-related aspects, business goals, IT strategy, business goals, etc. This is why it is of utmost importance to actively communicate between IT and business because being on the same page directly reflects in creating solution concepts and implementing the right one.

Requirement and delivery related complexities: One of the fundamentals of business analysis and even innovation in general is that no matter how senior, how expert, how experienced and eloquent users and other stakeholders are, never believe (fully) what they say about what their problem is, what their needs are, and how an ideal solution would look like. Rather, believe what they actually do, once you give them a working prototype or solution. This cautiousness not only questions the trustworthiness of the estimated business value, but can even question the validity of the requirement itself. What practical consequences does this imply?

- Always plan on the possibility that the requirement and the business value itself can change fundamentally! Expect that what they say is a crucial game-changer feature you developed for three months turns out to only happen in 0.1% of the everyday cases and will barely be used. Even expect that although you might have the best hammer in the world, not every problem is a nail…

- Try coming up with the cheapest and most easily and quickly developable minimal solution for the problem that is already usable and valuable. With this you can actually observe users’ behavior and reactions, which is a far more reliable source of estimating business value than any amount of interviews and discussions.

- Very often, it makes sense to deliver solutions in phases, for several reasons:

- You deliver value earlier for the users. The delivered development already starts to generate value while you are working on the later phases of it.

- You get valuable and more credible feedback from users.

- Users can change their minds or develop new ideas about how the feature or solution can and should be extended, improved, and developed further.

- You can change and develop the solution concept itself for the next phases, based on the new information and learning gathered.

- Taking this thinking a little further, we often realize that the good-enough level of business value is not even one line in our coordinate system, but more. There can be a good-enough solution for now, and then a year later, we should develop the solution to the next level because of some changing business circumstances.

In reality, this process – of creating different solution concepts for a problem and picking the right one of the several – very often happens in iterations. Instead of just going through the steps of the above workflow one by one, there are several iterations of generating concepts, discussions with users and customers, evaluating solutions, tweaking concepts, coming up with additional solutions until we have a solid set of options and solid bases for making a decision. To support this iterative process and guide our way and direction of thinking, I collected a handful of questions worth asking ourselves along the way:

- Can we do it much cheaper somehow?

- Can we do it slightly more expensive, resulting in a much bigger business value?

- Can we do it in separate phases to deliver something valuable earlier?

- How can we validate the solution as fast and cheaply as possible?

- What other hidden costs are there in the development of the different solutions?

- Is it worth looking for a higher business value solution?

- Is it even worth developing the good-enough business level solution?

Outlook

When prioritizing features and developments in a long backlog, these cost – business value estimations can be the basis of our decisions. Since our goal is to deliver as much business value from a limited amount of cost (for instance, the time and money cost of a sprint), development tasks compete with each other based on their cost and business value estimations. If other aspects are equal (which is rarely the case), then product owners should pick the tasks with the higher business value / cost ratio when defining the scope of a sprint.

I wrote this whole post in the context of software development, but this framework is much more general and universal, it can be applied to a whole lot of other areas and industries: anywhere where we invest something to build something to provide some value.

Conclusion

To summarize the main takeaways of my post in a few points:

- When trying to organize and rate solution concepts of a business requirement, think of both cost and business value dimensions

- Try to determine the good-enough level of business value expected

- Try to determine whether a solution’s business value is worth its cost

- Try to deliver something of lower business value first to gain more feedback and information, then move toward higher business value solutions if needed

And if you feel like this is all too complex and complicated in practice, don’t be surprised! 🙂